Developing a Culture of Reading for Pleasure 4: Reading Communities

21 August, 2023 Debbie Thomas is a Lecturer in Reading for Pleasure at the Open University, working to develop RfP pedagogy and research in schools across the country. She has also been a Regional Associate for The Centre for Literacy in Primary Education and previously worked as a local authority English advisor, a primary teacher, leader and inspector in a variety of different settings.

Debbie Thomas is a Lecturer in Reading for Pleasure at the Open University, working to develop RfP pedagogy and research in schools across the country. She has also been a Regional Associate for The Centre for Literacy in Primary Education and previously worked as a local authority English advisor, a primary teacher, leader and inspector in a variety of different settings.

In the last of a series of four blogs looking at the key findings of the latest RfP research, Debbie explores the social aspects of reading and the creation of communities of readers.

Developing the ‘will’ to read

We all know that instilling a love of reading in our pupils is vital, but how to go about it isn’t always straightforward, as the results from the 2021 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study makes clear. While young people in England scored well on their reading ‘skills’, this was not matched by their ‘will’ to read. Only 29% of young people surveyed said they enjoyed reading, compared to an international median of 42%, with pupils spending less time reading outside of school each day than in previous PIRLS cycles (2011 and 2016). The aim of this series of blogs has been to outline the research-informed approaches that can help us implement an effective and sustainable RfP strategy to reverse that trend.

Reading as a social activity

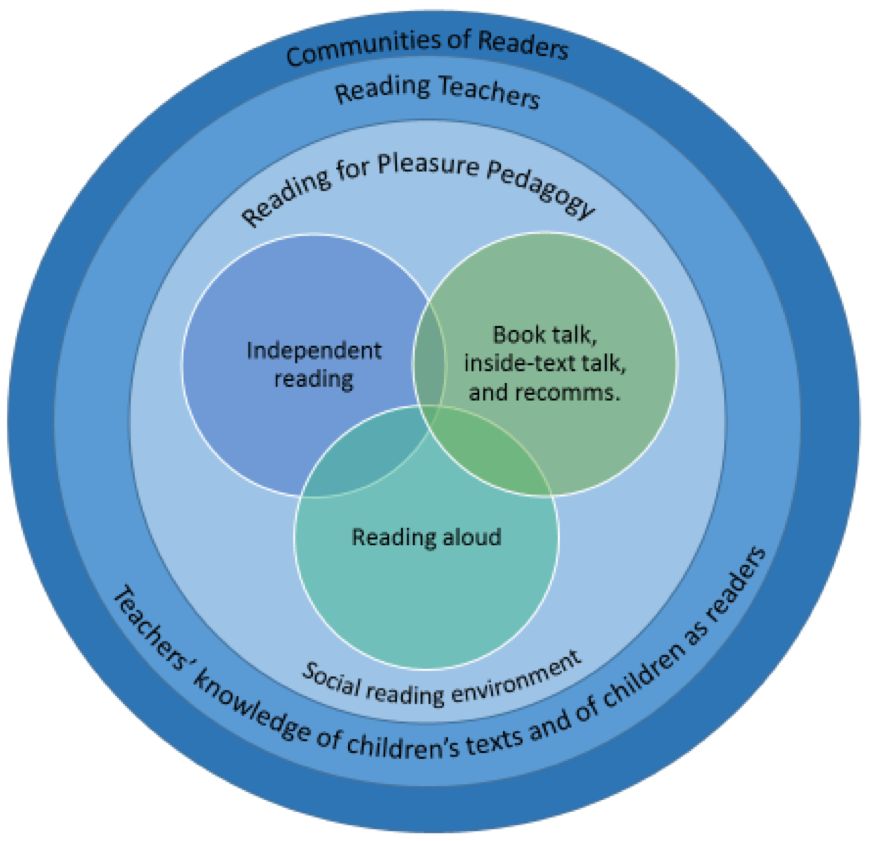

In the first two blogs – Teachers who Read and Readers who Teach and Children as Readers – we looked at the foundations of a strong RfP culture. We considered the importance of developing our own knowledge of children’s texts and understanding our pupils’ individual reader identities – their reading interests, habits and history. In the third blog we looked at key practices for the RfP classroom, including creating ‘books in common’ through reading aloud, independent reading time and informal book talk. These practices are all underpinned by the one of the most important findings from the seminal Teachers as Readers (TaRs) research (Cremin et al., 2014): namely the crucial role of book-related social interactions. Even though the act of reading might be solitary and every reader’s experience of a book is unique, having the opportunity to share our reading experiences with others is crucial in our journey to become life-long readers.

‘‘I see reading differently now – I’m not sure why I didn’t recognise how social it is – I just thought of it as personal book reading . . . that’s all changed’’ (Interview, teacher, Medway, from Building Communities of Engaged Readers, Cremin et al., 2014)

It is the social nature of reading for pleasure and the importance of building and developing reading communities that is the focus of this fourth blog.

Figure 1: Research insights regarding the effective development of reading for pleasure (based on Cremin et al. 2014)

Building reading communities

As we grow our repertoire of children’s texts, get to know our pupils as readers, recognise and share our own reading identity, and implement the RfP pedagogy, we will start to build a reading community – a group of people who connect through texts and reading. Reading communities are both the result of, and the space in which our RfP practice sits.

Characteristics of a healthy reading community

All reading communities are unique and distinct, shaped by their members and their needs. What is more, they are continuously adapting and evolving. Reading communities are more of a process than a fixed destination. While this may sound a bit messy and vague, we can at least identify key characteristics, drawn from the TaRs findings, that are common to all healthy reading communities:

- Everyone is invited – A healthy reading community has a space for all readers. Not just the keen, avid child readers, but those who are tentative or still unsure about their enjoyment of reading. It welcomes not just the Reading Teacher or Literacy Lead, but the reading volunteers, parents, TAs, reading ambassadors, and sports coaches.

- All kinds of reading are celebrated – In a healthy reading community, the rich variety of material that makes up reading in the 21st century is acknowledged and valued, from the latest book award winner to the catchy slogan on an advertising billboard.

- Reader choice matters – A healthy reading community actively encourages young people to follow and develop their own reading interests and habits.

- Book talk is central – Multiple opportunities, both formal and informal, for readers to share recommendations, discuss reading preferences and explore different reading experiences are a key feature of healthy reading communities.

- We are all readers – In a healthy reading community, the relations between members are defined by reciprocity and interactivity; there isn’t one expert or leader who takes control. Every reader has a part to play, and each reader’s unique reading identity is recognised and valued.

Nurturing our reading communities

How can we nurture these newly emergent communities of readers? Help them to develop, be recognised and supported? And perhaps extend them beyond the classroom and the school gates? There are three key areas to consider.

When we think of a ‘reading community’, it is easy to fall into the trap of thinking only in terms of bigger groups and planned activities. However, meaningful reading interactions can happen anytime and can involve just a couple of people. A group of pupils discussing the Beano in the playground, a class voting for their next read aloud title, pupils and parents enjoying a whole-school booknic; all of these activities provide equally valid opportunities for engaged talk around books and reading. It is vital that we recognise, celebrate and connect all these different reading interactions if we are to nurture our reading community and help it grow.

Understanding the particular needs of our pupils, school and setting is also a key factor if we are to help our reading community develop. Activities that work for one school might have very little impact in our setting, or even alienate the individuals we are trying to include. It is always worth exploring the many excellent examples of practice on the OU RfP website but keep the needs of your own reading community firmly in mind so that you can tailor the activities accordingly.

Building and sustaining a community of engaged readers takes time, planning and commitment. Ad-hoc activities may generate lots of excitement on the day but will not deliver life-long readers unless they are underpinned by a clear RfP strategy that includes ongoing support for teaching staff as well as opportunities for more formal CPD.

Reflect, revise, adapt

Reading communities are constantly changing and evolving and so must we as practitioners. Frequent, shared reflection needs to be built in to our RfP strategy, and our practices and activities constantly monitored and revisited to ensure that they have the desired impact. A ‘good idea’, for example, might encourage our keen readers to read more but, if it fails to engage our more reluctant readers, the result will be to create further division rather than community. While we may not be able to give a child’s pleasure in reading a score, there are tools that we can use to track the way that children see themselves as readers. Documenting these changes in reading attitudes and behaviours can then help us assess the impact and efficacy of a particular activity.

A necessity, not a luxury

We cannot make a child read for pleasure. However, we can create an environment in which reading is presented as enticing and engaging. The inherently social nature of reading means it flourishes where we are supported and encouraged by others. Given the vital role that reading for pleasure plays in ensuring that each and every child achieves their full potential, committing the time and resources to understand the principles and approaches that will allow us to develop communities of engaged readers is not a luxury but a necessity.

Further resources

- There are many celebration days, shadowing schemes and festivals through the year that can be used to introduce new authors, shine a spotlight on different kinds of texts and celebrate the power of books and reading. The Literacy Year calendar can help you identify the events that will best support your school’s RfP strategy.

- Join us at one of our regular OU Reading for Pleasure conferences for a day of engaging talks and evidence-based workshops led by expert practitioners. Details of the next conference in March will be released soon.

- The new Reading Teachers: Nurturing Reading forPleasure book combines the latest academic insights with practical case studies.

- Consider signing up for the OU’s free online Developing Reading for Pleasure course.

- You may also be interested to read how Holden Clough Community Primary School set about raising £12,000 to fund their Reading for Pleasure campaign.

First published in June 2023. Reviewed and updated August 2023.