Raising Writing Achievement & Engagement: The Freedom to Choose

20 November, 2024 Sam Creighton is a Y5 teacher and the Literacy Lead at Elmhurst Primary School, a four-form primary school in Newham, London. In 2023, Elmhurst Primary was named the UKLA’s Literacy School of the Year, recognising the school’s commitment to all aspects of literacy and its creative and engaging literacy curriculum.

Sam Creighton is a Y5 teacher and the Literacy Lead at Elmhurst Primary School, a four-form primary school in Newham, London. In 2023, Elmhurst Primary was named the UKLA’s Literacy School of the Year, recognising the school’s commitment to all aspects of literacy and its creative and engaging literacy curriculum.

For the last five years, Elmhurst has been developing and implementing an evidence-based Writing for Pleasure approach that has yielded hugely positive results. In the first of two blogs for Literacy Hive, Sam shares some of the practical steps that have been introduced to improve engagement and achievement in writing across the whole school community.

A New Writing Journey

If you rewind the clock five years, Elmhurst’s writing curriculum seemed to be incredibly successful. Year-on-year, our end of key stage results were well above national average, and these were always upheld in moderation. The saying ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ comes to mind: why mess with a seemingly winning formula? The reason we felt compelled to review our writing curriculum is that the research showed us – but, more importantly, we felt and could see on the ground – that we could be offering more to our children.

- Firstly, the enjoyment wasn’t there: writing felt high-stakes but also high-effort – for both children and teachers. This often resulted in a groan in both classrooms and the staff room when the ‘writing weeks’ of our literacy curriculum rolled around.

- Secondly, our children lacked independence: when children were asked to create a piece without the scaffolding of the teacher modelling each step, the quality of the outcomes dropped dramatically.

- Thirdly, the writing often felt monotonous and stale: 30 versions of the same piece, not one of which contained any clue to our children’s rich cultural histories and vibrant lives outside of school.

We knew this wasn’t as it should be. After all, at their core, writing lessons should be about developing writers, not producing writing. This means that the central aim is not to have each child create a specific piece of work, but rather to use this work as a vehicle to embed self-regulation strategies that allow them to be confident and competent writers both within and, most importantly, beyond school.

Putting Research into Practice

Putting Research into Practice

From the start, we knew that any changes that we made needed to be evidence-based. Few activities we ask our pupils to engage in are as cognitively demanding as writing. They must bring together a whole array of compositional and transcriptional skills, all mediated through their personal opinion of writing and of themselves as writers and drawing on their own stores of general knowledge. It’s complex, to say the least, which is why there is a wealth of research that focuses on effective methods for writing instruction.

One of the most useful research resources for teachers is the Open University’s recent report Reading and Writing for Pleasure: A Framework for Practice(1). The result of a three-year project (2020-2023) that included a systematic review of existing research and data collected from six London-based literacy projects, the report identifies a range of approaches that have been demonstrated to be effective in promoting reading and writing for pleasure. It can sometimes be hard, however, to see how such approaches can be implemented in the busy classrooms of even busier teachers. In this series of blogs, I would like to share some concrete examples of how the Framework’s headlines have worked in my classroom and how they could work in yours. I will touch on how to bring genuine purpose to writing projects, the role of the teacher in the writing classroom and how to build authentic writing communities. In this first blog, however, I would like to focus on the key role that agency and autonomy play in developing effective and engaged young writers.

Reading and Writing: Interconnected but Distinct Disciplines

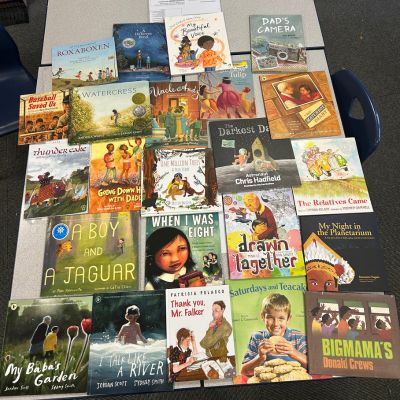

A key theme highlighted by the Reading and Writing for Pleasure: A Framework for Practice report is that ‘children are more motivated when the texts available are culturally relevant and connected to their lives and interests’. This means choosing texts to study, not because they give lots of opportunities for writing, but because they will excite and inspire the specific class of children in front of you. So, how can we choose texts that inspire writers, as opposed to ones that simply fit nicely into a scheme of work? Or – and this really is the Holy Grail – how do we find texts that do both?

At Elmhurst, the answer came in the form of a more systemic change: we split reading and writing into separate lessons (both taught daily), understanding that they are interconnected but distinct disciplines. Splitting reading and writing into separate lessons means that the topics of our writing projects are no longer dictated by the books we study, and we can offer pupils the freedom to choose their own topic based on their passions, interests and knowledge. It is at this point that many teachers raise an eyebrow. Surely, allowing 30 children to write on 30 completely different topics is a sure-fire recipe for chaos? It is certainly what lots of teachers at Elmhurst worried about when we made the shift. In practice, however, we have found that this autonomy has revolutionised our children’s enjoyment of and achievement in writing. There are a few measures we have put in place to make sure it works.

Freedom NOT Free-for-all

Freedom NOT Free-for-all

Firstly, freedom does not mean free-for-all. The approach that we have adopted at Elmhurst – called ‘genre study’ – defines the text type for each project. While all children write within a specific genre – whether that’s a setting-driven short story, a persuasive letter, or sensory poetry – they can each choose their own topic within this. To do this, children need to have a solid understanding of genre conventions (e.g. what a good explanation text looks like) and this is where we can include those inspiring, motivating, culturally relevant texts that the Framework for Practice refers to. We spend the first week of each project unpicking good and bad examples of our chosen genre, using a mixture of published texts, teacher models and work from previous cohorts of students. We pick this range of model texts to cover topics and ideas that will chime with our students, boosting their engagement right from the start.

Pupils use the understanding they gain from this analysis to co-construct the success criteria for the project with their teacher. When the children devise these learning objectives themselves we have found they are more invested and engaged. They understand not only what techniques and craft moves they need to include in their writing, but also why they are important. Having a clear understanding of the genre requirements also reduces the cognitive load when it comes to the drafting process later: because the children already know which writing techniques to use, they can focus more of their mental capacity on how to employ them for the benefit of their own composition.

Child-centred Rather than Book-based

One of the most important messages from the Framework for Practice report seems to me to be the importance of ‘foregrounding ... the voices of children and young people and seeking to understand their unique interests, lives, and literate identities’. Unfortunately, it is so easy for this to get accidentally forgotten in book-based planning. Sometimes, kids adore the book they are being asked to write an alternate ending or a character’s diary entry for, and then it’s magic for them to get to extend that literary world that they love. But what about those children who don’t love the book that is meant to be the springboard for their writing? For them, it can become a ball and chain holding them down.

Equally, if children are writing a letter as Davey from Cloud Busting(2) or a newspaper report of the landing of the Mars rover after reading Curiosity(3) (both of which are great examples of book-based writing that we use as part of our reading curriculum), they are only ever writing as the author of those books, doing their best to copy their voice and world view. This doesn’t give children the agency to speak as their authentic selves or to tap into the vast funds of knowledge that they have outside school, such as their religion, culture, hobbies and interests, life experiences, interpersonal relationships and family histories.

It is worth taking a moment to clarify the difference between the writing that takes place in our reading and our writing lessons. Our writing curriculum allows children up to half a term to pursue authentic, and often deeply personal, writing projects. In our reading units, children will have 2-3 days to produce a piece of creative writing inspired by the book they have just finished studying. While we understand that the latter is a great way to asses children’s comprehension of the books, we feel it cannot give a true insight into the child’s development as a writer, as they are not able to go through all the different writing processes or to fully engage their own writerly voice.

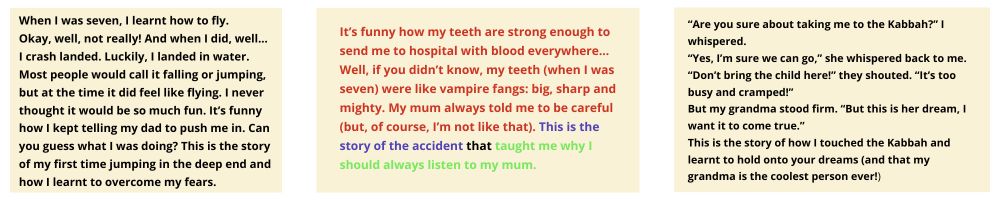

Memoir writing, Year 5

Helping Children Find Their Authentic Voice

Real authors write about topics that they care about, so why shouldn’t our pupils have the same opportunity? After all, it is always less engaging to write about someone else’s interests than your own. I have met many teachers who (understandably) say something along the lines of: ‘Well this is a lovely idea, but it would never work for my kids because they wouldn’t have any ideas/they don’t know enough about anything’. I understand the reticence and the worry – I definitely felt it myself at one point. To address this, we spend time (usually 2-3 lessons) at the start of a project equipping children with strategies to generate their own ideas within the chosen genre. Our experience has been that children generally come up with multiple ideas and an important part of this activity is actually helping them to sift through and find the most interesting and viable subjects to develop. To give an idea of the range of subjects that children come up with when they are granted some autonomy, here are a few examples from my class last year.

For setting-driven short stories, children could write any narrative set in West Ham Park. We had:

- A child leading a protest march through the park.

- Someone discovering a dragon’s egg in a bush.

- An old man remembering joyful memories in the park from his childhood.

- Someone getting locked in overnight and freezing to death after falling in the pond!

For explanation texts, children could choose any topic they were an expert on. We had:

- Why do Muslims pray five times a day?

- Why is Liverpool the best football team?

- How do you fix your broken code on Scratch?

- Why is Nadia Hussain an inspiring role model?

Writing Lessons are for Writing!

As I said at the very start, writing is a cognitively demanding process. Expecting children to get to grips with a new topic, while also trying to learn how to write in a new genre effectively can lead to overload, with poorer writing outcomes as a result. When I first taught Y5 at Elmhurst, all the children had to write their explanation texts about Komodo dragons. On the one hand, this was easy because we could watch bits of documentaries and read fact-files together in class. On the other hand, it was dire because no one really cared that much (or knew anything!) about Komodo dragons. I had to teach as much about the animal as I did about the writing of the text. The kids gave their piece a good stab but it was essentially 30 children recreating 30 versions of my model using mostly the same information we had found together or that I had provided. Letting children tap into topics they are already an expert on has, not only boosted their confidence and enthusiasm, but also freed up my teaching time to focus on the writing techniques I want them to master – which is what writing lessons are meant to be about, after all!

The Reward is Worth the Risk

The journey we have undergone at Elmhurst has been a long one. More importantly, it is one that is ongoing. It is a course charted by research, particularly that from Ross Young and Felicity Ferguson at The Writing for Pleasure Centre. However, even in the trickiest moments (and there have been a fair few!), our shared vision to empower our children to find, develop and use their own voices, and the enjoyment they now draw from being writers, has helped us to hold firm. The decision to allow children real autonomy and choice is undoubtedly a scary one – the thing about kids is that they won’t always make the choices you want them to! – but it is how we can free ourselves up as educators to focus our expertise, not on controlling children’s writing, but rather on developing them as writers.

Now read Sam’s second blog, Creating Communities of Writers, in which he talks about making time to write, the role of talk and creating a sense of audience and purpose for young writers.

Notes

(1) Reading and Writing for Pleasure: A Framework for Practice, Teresa Cremin, Helen Hendry, Liz Chamberlain & Samantha Hulston (2024).

(2) Cloud Busting by Malorie Blackman (Yearling)

(3)Curiosity by Markus Motum (Walker Studio)